A child can learn to be a person or a package

Parents have a role to play in the shift out of car dependency. Give kids freedom to be physically active and opt out of unhealthy mobility.

As I’m researching and interviewing for my unhealthy infrastructure documentary, I come across stories and studies that could take this film in a hundred different directions. I’ll share snippets on Twitter and LinkedIn, but this right here—Urbanism Speakeasy—is the place for context about how all these things relate back to the big picture of forming and maintaining happy, healthy communities.

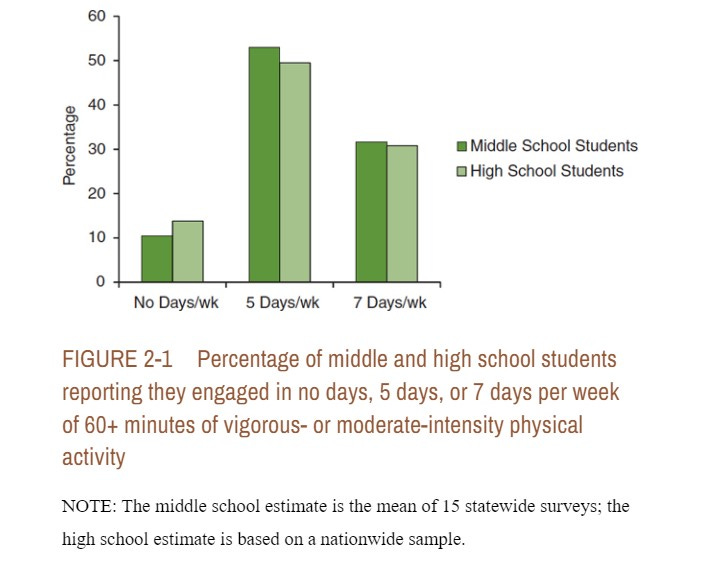

One of the issues worth unpacking is the low level of physical activity among American children. The Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion periodically updates its Physical Activity Guidelines. It’s easy to nod and smile at the types of recommended activity because the recommendations hardly seem like a stretch.

But the CDC says under half of our kids get the baseline activity they need. The chart below is from Educating the Student Body.

One obvious hurdle is the number of hours kids are expected to sit in a chair at school. The older they get, the more sitting is expected. Changing school culture is going to be extremely difficult in the U.S., because we’re so conditioned to think we’ve got it figured out.

Mobility before and after school is a different story. (Or at least it can be.) There are ways to change mindsets about how we move around the built environment, starting in the early years.

Listen to the two soundbites below about normalizing independence. I’ve included transcriptions that were lightly edited for clarity.

Lenore Skenazy is the founder of Free-Range Kids, and president of Let Grow, the non-profit promoting childhood independence.

Independence is getting on a horse and delivering the mail, independence is walking to school, independence is playing flashlight tag at night. But it's also doing almost anything on your own. And yet, we're asking the teachers to do things like tie shoelaces for kids so routinely that teachers just do it.

It shows me that something had changed dramatically in childhood. It's good for kids to struggle a little and do things on their own, but now they can't do that if we're always with them. So, really, if you want to have independence in childhood, you have to re-normalize the idea that kids can be without adult supervision some of the time.

They're going to get into scrapes, and they're going to get a little hurt, they're going to get lost or confused or sometimes cry or sometimes come home and need a bandage. That's okay. The alternative is basically having a child in a bell jar that you are delivering.

I sometimes say kids have become FedEx packages that we drop off at school, and then pick up at 3:30, and then we have to get to Kumon, and then there's soccer. And then of course there's homework help, and there's the reading log and pretty soon the kid is without agency because it's an adult who's always making everything happen and observing while it goes on.

Accidentally, with the best of intentions, we ended up taking all the independence out of childhood and replacing it as an adult run program. We’re optimizing for us, even as the kids are doing something very teachable and important, and possibly to put on their resumes later on when they're trying to get a scholarship or go to college.

They don't have time to just goof off, screw up, have fun, and become a person instead of a package.

Dr. Mickey Witte is a neuroscientist, university lecturer, and road safety advocate. She publishes Mickey Eats Plants.

People think getting in 30 minutes, 40 minutes, 20 minutes, whatever it may be of activity a day—meaning committed, physical activity at a gym or running around their neighborhood—that's to them activity. The bigger picture of how we move about our world as part of physical activity is neglected.

My background is in neuroscience, where I've studied obesity and brain mechanisms as they relate to metabolism, body weight, regulation, and ingestive behavior. I want to understand the bigger picture as to why we are obese. I teach a course at University of Miami and I wrote on the board, “Why are we obese? Why do we have this epidemic?”

We had a full board of answers with factors that went into obesity. Not one of my undergrads thought of physical environment or built environment.

I led them there. I said, “I'm looking for physical environment. What about it?” Nobody got it and I was floored. They had lots of other reasons like industry, portion sizes, processed food, but the idea of our physical environment as a reason was just completely over their heads. And so I think there's a disconnect.

The average person doesn't see the obesity crisis linked to the fact that we have car dependency. People just think that that's a necessary part of their life. They don't make that connection, but once you see it you can't unsee it.

Once you understand that your city, your environment, your county was built with the car as the primary level of service—you can’t unsee it. It takes breaking down that assumption that people have that this is just how we live. We sit in traffic for 45 minutes to commute. We sit in traffic to go a mile down the road to CVS. It's just wild to me.

There's research backing up the connection between active transportation and quality of life, both in adults and in kids. I'm in the middle of writing a manuscript having to do with parental attitudes around allowing their children to bike to school. And in my background literature review, I've pulled a ton of papers, many of which show kids who use active transportation to get to school have lower BMI, better grades, and also report being in a better mood than they're non-active transportation peers.

There’s a body of evidence showing how good it is for overall health to be active.

My boys are 19 and 17 now, so their form of “free range” is much different than the early years of childhood. But I’ll admit, they didn’t get to experience even a fraction of what I did as a neighborhood roamer in the 80s and early 90s. I’m not saying that as a Gen X brag, but as a parenting failure.

Did you have the freedom to be physically active when you were growing up? What about your kids? Drop a comment below.

I walked and biked to school when I was a child. As a teen, as soon as I turned 14 suddenly I was needed much more at home to parent my sister while my mother worked and I was forbidden to go out in the evening or at night because good children didn't leave the house. Those years to me were like prison. I saw what was happening to parents being more obsessive over their children and once I became an adult I opted not to participate in the whole child-rearing thing. I wasn't willing to imprison my own children.