Daylighting the blind spots of journalism

Editors and reporters make it hard to tell if they’re in the business of exploitation or exploration.

Before I rant, take a look at these headlines.

In standard media outlets, the author of an article doesn’t write the headline, the sub header, or the call-out text boxes. That’s up to editors and other copywriters. Still, I regularly find myself in confrontations with journalists on social media about story framing (e.g. “boy collides with truck” rather than “man driving truck kills boy riding a bicycle”). The moment they respond, it becomes abundantly clear if the journalist possesses any amount of intellectual curiosity for the topic they themselves wrote about.

A curious journalist doesn’t simply report on what’s easy or obvious; they explore the nuances, the overlooked or hidden perspectives, and the “why” behind the “what.” Some might say that’s not what a curious journalist is supposed to do, it’s what a journalist is supposed to do.

I recently posted a news story on X about a new California law. As ridiculous as the print headline was, the video was even more entertaining because you get to hear people in their words explain that convenience is more important than safety.

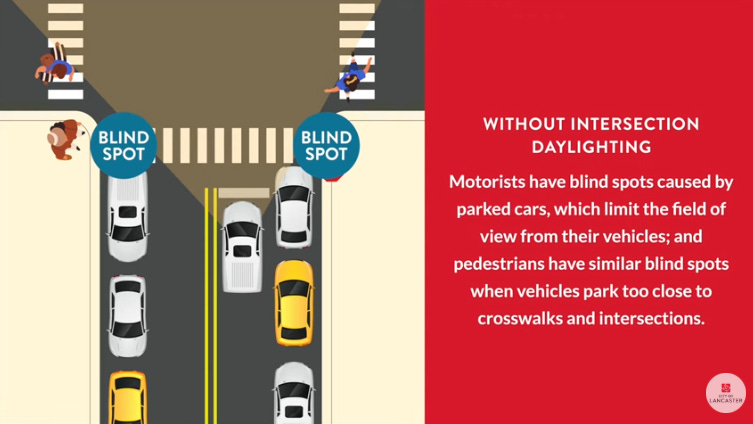

What a dilemma. On the one hand, human lives could be saved. But on the other hand, car storage would be lost. Here’s a handy illustration from Lancaster, PA describing why parking spaces are removed.

Daylighting is getting rid of the blind spots at the corners of intersections. So in an environment where people are going to be crossing the street, you can imagine how important it would be for everyone to see around corners.

And here’s how someone on X reacted to the loss of parking sob story:

As a journalist I work on facts not conjecture. Can you show me the stats showing lives were taken as a result of cars parked near crosswalks? As a pedestrian I’ve nearly been hit walking IN crosswalks in SF by cars that don’t stop at stop signs. That’s a much bigger issue.

—Susan Dyer Reynolds, Cofounder, CEO, Editorial Director, The Voice of San Francisco

I pushed back.

A journalist might be curious about SF's claim that daylighting reduced crashes by 14%.

A journalist might be curious about whether there's any connection between "the pedestrian came out of nowhere" and poor visibility around corners.

over three decades in SF as a pedestrian, and the dozens of times I have nearly been hit had to do with cars running stop signs when I was in the crosswalk.

Reynolds showed her hand:

And I am currently looking through all the data for a story but “daylighting” isn’t in the stats because it hasn’t started yet 🤦🏻♀️

Don’t you have enough to worry about 3,000 miles away? No one cares what you think.

Social media engagement tip: When someone responds like this, they aren’t interested in a good faith exchange of ideas. They know they’re correct and no amount of data or studies from you will change the fact that they’re correct. For cases like these, I opt for toying and/or trolling. Her first comment shows she isn’t serious about the issue if she’s willing to pretend like there’s no California data on the safety effects of daylighting because the new statewide 20-foot enforcement law hasn’t begun yet.

I responded:

"Do my job for me," insisted very serious journalist.

Reynolds, a journalist, editor, owner of a news publication, had this to say:

You’re the one making the claim from 3,000 miles away. Your insipid response tells me that you have zero stats to make your case.

Like I said, people posting like this aren’t interested in stats. I’m not going to change her mind, but sometimes other people read the comments and learn something. It also gives an ejection seat option if the poster has a change of heart and decides you have something to offer from 3,000 miles away. So I offered a few questions I’d ask a reporter in a newsroom:

What is it about a West Coast city that makes street design and driver behavior different from an East Coast city?

Which research about daylighting did you explore?

What is line of sight and what does it have to do with traffic safety?

What are blind spots?

What is line of sight?

How do "pedestrians come out of nowhere"?

Why do 43 states keep people from parking on intersection corners?

Her final strategy was to simply move the goalposts:

My 3,000 miles-away-activist guy: We have much bigger issues to deal with when it comes to people dying. Can you stomach this video? It’s the still-limp body of a man who died on the sidewalk from a fentanyl overdose being loaded into a body bag, one of over 600 so far in 2024.

“We shouldn’t waste time helping these people because those people over there also need help.” It’s no wonder the average person reading traditional media coverage of traffic safety has a ho-hum, thoughts-and-prayers attitude about proven ways to reduce crashes and save lives.

Journalism should involve intellectual curiosity, not this "hand me the files" nonsense put proudly on display by the owner of a news publication. The internet is amazing. It's not hard to find information about why storing vehicles on street corners is dangerous, so there’s no excuse for this sort of behavior. I don’t get into exchanges like this every day with reporters but I do see headlines every day that deliberately distort or misrepresent a real story.

When municipalities implement traffic safety initiatives, media coverage often frames the story in terms of inconveniences for drivers. The attention is on the potential nuisance rather than a life-saving intervention. Any 21st century reporter could access the internet and discover in seconds that not parking in crosswalks and at stop signs has been shown to reduce collisions at intersections by double-digit percentages in some cities.

Beyond the data, there are human stories that would appeal to viewers and readers:

A student who is now safer walking to school.

A senior citizen who can now cross the street without fear.

A delivery truck driver who isn’t terrified to maneuver city streets.

It’s a shame that so many journalists seem to be rewarded for reinforcing biases. It’s not sustainable for their career anymore, since readers and viewers can fact-check in real time. Readers and viewers aren’t expecting every reporter to be an expert on every topic—that’s not what makes the greats great. Here are a few tips to cultivate intellectual curiosity:

Challenge assumptions: If a story seems straightforward, ask what might be missing. Who benefits? Who is harmed?

Find primary sources: Seek out studies, reports, and expert opinions that provide context and evidence.

Steelman the opposing view: Even if you think it’s morally wrong to outlaw parking in crosswalks, describe how someone who thinks crosswalks should be clear got to that point of view.

The point of intellectual curiosity isn’t to convince someone that you’re right and they’re wrong. It’s almost the opposite mindset. Assume you have much to learn about a topic that intrigues you. Be skeptical, even of your own held beliefs. Love learning.

The illiterate of the 21st century will not be those who cannot read and write, but those who cannot learn, unlearn, and relearn.

—Alvin Toffler, futurist

Here's your free copy of NEIGHBORHOOD CHARACTER

What started as an idea for a traditional 12-month wall calendar, turned into a riff on the daily affirmation genre. If SNL’s Stuart Smalley was a NIMBY, he’d be reading my new book, Neighborhood Character: 365 Daily Affirmations for Defenders of the Status Quo

I think it inevitably boils down to they are drivers themselves and have a vested personal interest in not seeing parking reduced! Much like the vaunted small business owner who drives into work believes a bike lane will do nothing but demolish their business.

Journalists (writers and editors) depend on insiders as sources for background, facts relevant to the story, and often direct quotes. Many media critics characterizes this relationship as sources selling access in exchange for favorable reporting. Get your story from the cop at the crash scene, write around what the source said, and file the story. Job done. The cops themselves are car dependent themselves are disposed to believing the driver's point of view, while journalists are also car dependent, so they are disposed to believing the cop for the same reason the cop believes other drivers. And the journalist needs the cop as a source. Now you are providing data to the journalist that conflicts with how they do their jobs and conflicts with the narratives of their sources. "It's hard to get someone to understand something when their salary depends on them misunderstanding it."