Fundamentalism in urbanism

People will cling to beliefs, in spite of evidence that disproves their beliefs

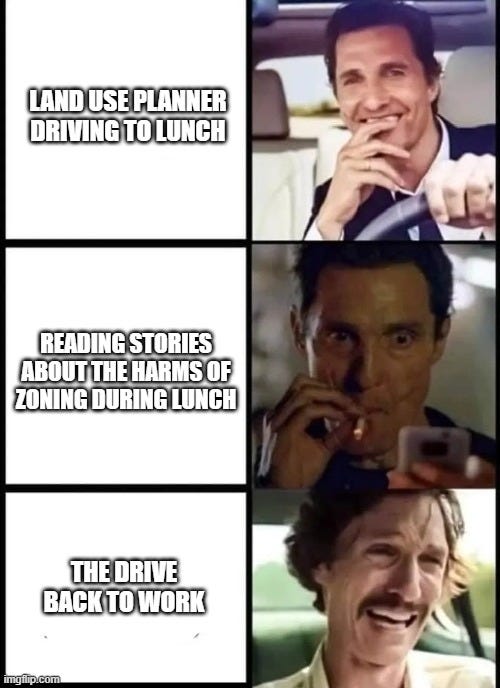

Claim: Zoning helps more people than it hurts.

Evidence: Zoning hurts more people than it helps.

Planning Industry: Let’s keep trying more zoning.

No amount of evidence can shake the resolve of a fundamentalist.

For decades, a rigid and unquestioning faith in zoning has shaped America’s countryside: small towns, big cities, suburbs, and rural areas. Zoning—the practice of separating land uses into distinct categories—is a fundamental tool of professional planners to assign land uses where they ought to be.

Of course, the rub is why should they dictate where to allow homes, parks, schools, churches, grocery stores, and offices. And why should they dictate what you do inside your own property as long as it isn’t harming others? (Self-employed hair stylists operating out of their kitchen without permission or permits is one of many facepalmy examples of zoning violations.)

Even as evidence mounts that land use restrictions have for decades directly and negatively impacted housing, transportation, personal wealth, and local economies, the faith in zoning remains remarkably unshaken. In fact, rather than reassessing zoning’s role in our cities, many planners, policymakers, and residents continue to cling to it with almost fundamentalist zeal.

“How did you go bankrupt?” Bill asked.

“Two ways,” Mike said. “Gradually and then suddenly.”

—Ernest Hemingway, The Sun Also Rises

Thomas Kuhn was a philosopher whose groundbreaking 1962 book, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, is credited with bringing the term “paradigm shift” to pop culture. Kuhn described how scientific communities stick to established paradigms, even as evidence of their limitations mounted. Widely accepted paradigms for understanding and interpreting knowledge don’t crumble under the weight of mere data. Instead, they tend to persist until a crisis emerges—when anomalies become so disruptive that a shift to a new paradigm is unavoidable.

In Hemingway-speak, the gradual part of reform is happening. Missing middle housing, for example, has been energizing ordinary voters against the notion that townhouses and single-family houses can’t exist on the same street. Magazines and blogs for planners have been covering the possibility of tweaking land use restrictions here and there. But America’s zoning reckoning (Hemingway’s suddenly or Kuhn’s paradigm shift) is still on the horizon.

The crisis takes a much longer time coming than you think, and then it happens much faster than you would have thought.

—Dr. Rudi Dornbusch, MIT professor of economics

Thomas Kuhn described “normal science” as a dominant model that shapes assumptions, practices, and even what is considered valid knowledge. Zoning was established in the early 20th century as a way to protect homeowners from unwanted industrial developments nearby. It was pitched as a way to separate heavy industry from residential neighborhoods, which made practical sense at a time when factories polluted neighborhoods. Early industrial cities were notorious for their noise, filth, sickness, and all around misery.

The wealthy had options, so they’d put some distance between themselves and factory life. You can imagine that the elite would want to guarantee never having to deal with the industrial riff-raff. Zoning would give such guarantees. You can also imagine that social workers and other empaths would want to guarantee the poor and middle class had the same separation from the dirty parts of a city as the elites had. Zoning would give such guarantees.

But zoning wasn’t used merely as a tool to separate heavy industry from residential zones. Local power brokers segregated all the land uses—separating single-family homes from apartments, office buildings from retail, residential from retail, and so on. The regulatory framework became so normalized in America that it’s hard for people to imagine life without it: “Without zoning, my neighbor might build a strip club and a paper mill.”

Normal Science, the activity in which most scientists inevitably spend almost all of their time, is predicated on the assumption that the scientific community knows what the world is like.

Much of the success of the enterprise derives from the community’s willingness to defend that assumption, if necessary, at considerable cost.

As Kuhn would’ve predicted, the normal science of zoning has produced a number of “anomalies” that increasingly contradict zoning’s purported benefits. Some of the most glaring anomalies include:

Housing Expense and Shortage: By restricting a variety of housing sizes and types, zoning codes limit the supply of housing, driving up prices and making places unaffordable for many residents. Desirable cities across the country are facing housing crises, where even middle-income families struggle to find affordable places to live. Their local land use rules prevent housing providers (developers, gasp!) from providing much-needed housing.

Environmental Degradation: Zoning encourages urban sprawl by pushing residential development outward into zones that are only practically reachable by car. Sprawl makes Americans dependent on personal automobiles, which means people are driving all the time for everything. No matter what a tree-hugging planner might tell you, zoning codes create low-density, car-centric development, at great expense to our natural environment.

Social Segregation: Zoning is a devilish way to lock the poors with poors and the rich with rich. Throughout history, the best cities had opportunities for people from all walks of life, social standing, and economic standing. If it was legal for a property owner to convert their single-family home to a duplex or fourplex, and legal for a grocery store to be built on the corner of a residential street, lower income households could live and work with everyone else.

Economic Stagnation and Opportunity Costs: By prohibiting a mixture of land uses in a neighborhood, zoning limits economic activity, making it difficult for small businesses to thrive in residential neighborhoods or for residents to access amenities without a car. Local governments don’t like to speak up too often about their tax revenues, but let’s face it, financially vibrant neighborhoods allow a variety of land uses.

Car Dependency. Neighborhood pharmacies are outlawed, so you drive to CVS just to get a birthday card. Neighborhood restaurants are outlawed, so you drive your kids to Chick-Fil-A. Neighborhood salons are outlawed, so you drive to get your nails done. Owning expensive tools and being dependent on expensive tools are very different. For most of the country, zoning is a mandated money pit.

Ageism. Stories like the one below are an outcome of zoning. An 88-year-old drove into a store and hurt 8 people. These crashes will increase as Baby Boomers age if land use policies keep preserving car dependency. Older adults need viable mobility options. You might even say that status quo zoning discriminates against the elderly.

For all its harms, why does the zoning paradigm remain so resilient? Kuhn argued that paradigms are more than just intellectual frameworks. They’re ingrained systems that shape professional practices, institutional structures, and social norms. Changing a paradigm isn’t just about accepting new facts, it’s about challenging an entire worldview, and that’s something humans are generally reluctant to do.

Embracing zoning with almost unyielding devotion looks a lot like fundamentalism.

Much like a fundamentalist belief system, zoning has developed a language of justification that makes it difficult to challenge. Clever defenses like “preserving neighborhood character” or “protecting property values” are invoked to defend restrictive zoning policies, even when these policies have been proven to harm the vast majority of people. Zoning defenders use language not to inform, but to deflect and manipulate.

Very few Americans are going to publicly say, “I believe the government should tell us where we’re allowed to build a townhouse” or “I believe the government should shut down home-based piano teachers for operating a business in a residential zone.” They have to use language to divert attention away from what zoning exists to do.

Clinging to the zoning paradigm in the 21st century looks less like pragmatism and more like dogma.

Kuhn would say a paradigm shift requires a moment of crisis, a point at which the old framework can no longer explain or accommodate the reality of a situation. We’re getting there with zoning. The accumulating anomalies are becoming too severe to ignore. I think it’s safe to say paradigm shifts are disruptive but necessary, but it’s professionally dangerous for a planner to say a foundational part of their industry needs to be upended.

The smart way to keep people passive and obedient is to strictly limit the spectrum of acceptable opinion, but allow very lively debate within that spectrum.

—Noam Chomsky, The Common Good

Breaking free from zoning fundamentalism won’t be easy, in large part because of what’s in the spectrum of acceptable opinion and what’s allowed to be debated. Like Chomsky says, planners are fine debating issues like whether a proposed restaurant will generate X car trips per day or X+100 car trips per day. But abolishing the rules that prohibit people from converting a garage to an apartment or music studio? Abolishing the rules that prohibit low income families from living car-free or car-lite? Not a chance.

Scientific revolutions reshaped how we understand the world. A zoning revolution has the potential to transform our small towns, big cities, and sprawling suburbs in positive ways we have yet to fully imagine. We have 100 years of evidence that zoning has brought more harm than good. Getting our local leaders to break out of the zoning paradigm is easier said than done, because data alone is not going to shake a fundamentalist. How are your storytelling chops coming along?

Re: "Zoning was established in the early 20th century as a way to protect homeowners from unwanted industrial developments nearby. It was pitched as a way to separate heavy industry from residential neighborhoods..."

Zoning was also used to keep out lower-income residents and people from different races. Paul Groth's history of SROs and boarding houses shows that the zoning laws used in 19th-century and early 20th century SF against rooming houses were ostensibly about safety but the real goal was to keep out low-income people and Chinese immigrants (among other groups).

[Groth, Paul. Living Downtown: The History of Residential Hotels in the United States. Chapter Four—Rooming Houses and the Margins of Respectability. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994.]

Issue just came up locally (pun) ... turns out strip clubs are often built near neighborhoods with or without zoning. I'm not saying that's good or bad. But people live just about everywhere now days. When they tried to apply a 2000ft buffer to this ordinance for sensitive stuff like schools, housing etc, they were left with nowhere to build. Apparently, that's a no-no in terms of overly restricing what this county deemed "sexually-oriented business." Ultimately they went with 1000 feet. https://www.williamsburgindependent.com/p/news-york-county-supervisors-restrict-adult-sexually-oriented-business?r=46dse3