Groupthink

It's socially awkward to challenge the beliefs and assumptions of our own groups

Groupthink is a psychological phenomenon where the desire for unanimity leads to irrational decision-making or position-taking. It’s powerful, especially for a culture like ours that teaches and rewards conformity from the time we enter school.

Planners and engineers go through 16+ years of conformity training. After all that schooling, it's socially dangerous to be a critical thinker. Even (maybe especially) during the higher ed years. Here’s the standard output of good conformists:

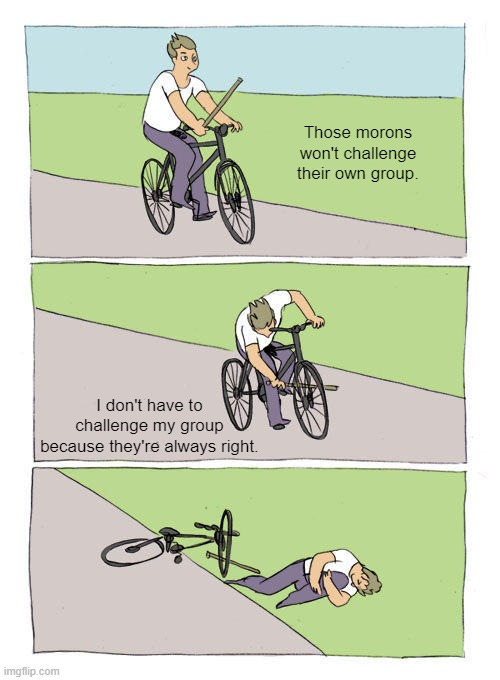

It's easy to spot Groupthink when it happens in groups with opposing views to yours, because from the outside, the flaws are glaring. We watch those guys move in lockstep, making ill-informed claims, approving shortsighted policy, and we congratulate ourselves for being wise, independent thinkers.

It's a human feature, not a bug, to recognize someone else's flaws before spotting our own. I imagine I’m not the only advocate or activist (of any issue, but I’m thinking about urbanism) to quickly spot collective rationalization, dismissal of dissent, overconfidence in inherent rightness, while missing it in myself. That’s dangerous because it leads to feeling a sense of superiority, which is socially repellent and makes an audience focus on the holier-than-thou messenger rather than the (ok, yes, holy!) message.

One of the best ways to guard against Groupthink is to stay curious. When you hear or read some new shocking information from a trusted source, start with "Wow—is that true?" or “How did you connect those dots?”

If your media consumption is like mine, you subscribe to far more podcasts and newsletters than you could ever keep up with. I’m trying to be deliberate about having some percentage come from a worldview that’s vastly different from my own. Reading content from Car & Driver and Automotive, for example, gets me asking questions about the insane acceleration of electric vehicles and built-in speed limiters. Asking questions and thinking about trade-offs sometimes puts me at odds with environmental advocates promoting the shift from ICE to EVs.

We should challenge each other with difficult urbanism topics. Not for the sake of demonstrating rightness, but for the sake of finding the best paths to human flourishing.

I would love to see a traveling conference or forum where people whose work directly shapes the built environment were in a Socratic circle with an audience. The moderator could guide a discussion in the Socratic method—not your standard dull presentations—followed by audience questions.

Land use planners, right-of-way administrators, land use attorneys, civil engineers, multimodal planners, economic development offices, financial institutions, planning commissioners, transit operators... there's more than enough types of people to participate.

Vigorously debate the ideas, not the people. Challenge the fundamental assumptions of your own group.

A forum or conference could be loosely organized following basic principles as opposed to some heavily branded and overthought production. I think the biggest obstacle to something like this is the reason it's so needed: our culture of conformity that leads to Groupthink.

In attendance should also be the workingclass parents, school age children, and elderly belonging to those groups who are disproportionately slaughtered by the current built environment and the resultant driver supremacy.

You have that pic of the mega road as an example of groupthink, and I agree. But I think it goes much deeper and is more invisible than that. Take ADUs. No great world city is filled with single family homes that have ADUs in their back yards. There are no ADUs in Paris, Barcelona, etc etc. But the more progressive, forward-thinking, YIMBY cohort treats ADUs not as a stepping stone to a better future but as an end in itself. You see this again and again with things like bike lanes, infill, zoning reform, etc etc. If you criticize an ill-used bike network, you're assumed to be a shill for cars not a pro-bike pragmatist who thinks results matter more than intentions.

There's very little discussion of how modest today's reforms are, or — critically — how on their own they will not get car-dependent American cities anywhere near the true goal of being more genuinely walkable. There's a bunch of old planners and engineers who are stuck in the 20th century. But there's a younger cohort of more progressive people who have lost sight of the end goal and resist critical discussions of how to make big changes.