Happy, healthy communities aren't made from being stuck in yesteryear's mindset

Learn from the giant leaps in art & science to improve your urbanism work.

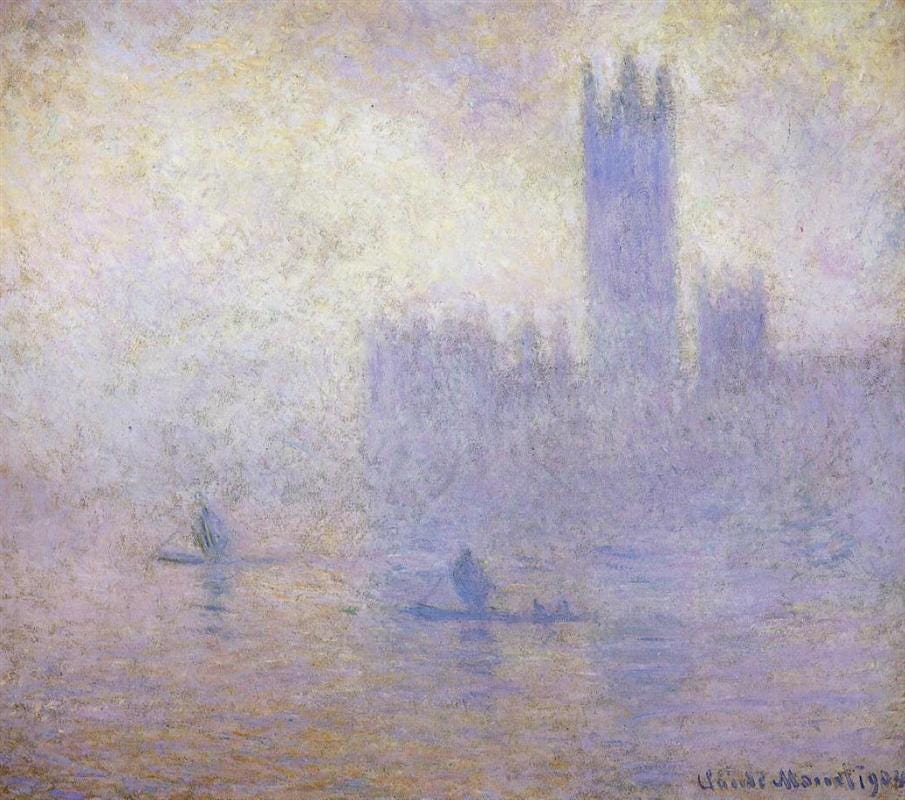

“Without fog, London would not be beautiful.” Claude Monet

Impressionist painters didn’t discover fog. It was always there, but it wasn’t something people were discussing much in the early 19th century leading up to the impressionists and tonalists. Each of those artistic movements created illusions of reality with familiar scenes.

James McNeill Whistler was an influential figure and one of the original tonalists. Here’s what he had to say about finding inspiration from natural elements previously left off the canvas:

And when the evening mist clothes the riverside with poetry, as with a veil, and the poor buildings lose themselves in the dim sky, and the tall chimneys become campanili, and the warehouses are palaces in the night and the whole city hangs in the heavens, and fairy-land is before us—then the wayfarer hastens home; the working man and the cultured one, the wise man and the one of pleasure, cease to understand, as they have ceased to see, and Nature, who, for once, has sung in tune, sings her exquisite song to the artists alone.

The day before, Londoners looked around through the mist and fog. Today they were listening to Whistler lecture about beauty and intrigue all around them.

Claude Monet is probably the most famous of the impressionist bunch. Once he stumbled into the London fog, his focus shifted from clear objects to the effects of atmosphere and light. Critics would argue about deeper meanings, whether impressionism was creating a dreamy or nightmarish mood for London, angelic or demonic.

But the meaning (or lack thereof) isn’t what got me thinking about these 19th century art movements. It’s the idea that something was always there and it took artists to draw the attention of normies to it.

300 years before Monet and Whistler, Nicolaus Copernicus was making the shocking case that Earth and other planets revolved around the sun, rather than Earth being the center of everything. He didn’t get everything right. Copernicus had no concept of gravity, so he wasn’t clear on how the celestial blobs swirled around each other or why they all orbited the sun. Not many decades later, Isaac Newton watched an apple fall out of a tree. He organized his math homework and philosophy into laws of gravity that were eventually used to describe planetary motion.

In hindsight, it seems almost childish to talk about major leaps in art and science because the advancements seem so obvious. Of course this foggy picture with shadowy figures in motion makes me feel uneasy. Of course gravity makes things fall to the ground.

Generations ahead of us will probably read stories about our era that begin like this: “Once upon a terrible time, America’s most educated city planners were convinced that cities optimized for motor vehicle traffic would be the safest and most prosperous.” Things that don’t even cross our minds today as possible outcomes will be boring in their obviousness later.

Consider space:

In 1960, science fiction was the only reasonable place for stories about a group of humans traveling beyond our atmosphere, circling the globe, and returning safely in their ship.

In 1961, Project Mercury launched multiple such voyages, making all sorts of discoveries about how people and machines function in weightless environments..

Consider music:

In 1965, anyone interested in hearing a new band had to either listen live to one of a few radio stations, or suffer through a friend’s attempt to sing.

In 1966, the portable cassette recorder was introduced, making it possible for anyone to make and play recordings without cables and microphones.

Consider city planning:

In 2022, land use planners and politicians still worked under the assumption that the social and physical harms of zoning were necessary and would always exist.

In 2023, a brave local planning department liberated its community from the crushing burdens of zoning, becoming a model for others to follow. (Maybe.)

J.F. Martel writes and podcasts about philosophy, art, and weird stories. When describing his book Reclaiming Art in the Age of Artifice, he emphasizes the importance of curiosity that leads to a love of learning. I’m sure confirmation bias is partly why I enjoy Martel’s ideas, because he says talking and making are incredibly important parts of the learning journey. Two of my favorite things are good for me? Tell me more!

Talk with people who have no professional interest in urbanism. Start a conversation around big What If questions that urbanists might think are off limits. Use a camera or microphone or keyboard to make something related to happy, healthy living.

Maybe your talk/make routine will unlock some creative way to build a better neighborhood, either physically or through policy. There’s no reason to always be operating from a yesteryear mindset with issues like affordable housing, traffic engineering, parks planning, and intersection design.

I don’t know if urbanism is science or art, but I do know its outcomes are best with a dose of creativity.