It's about time engineers included the cost of traffic violence in their calculations

Guest post by Sam Sklar, author of Exasperated Infrastructures

Sam Sklar is exasperated. He's been a transportation planner for almost 8 years and has been writing about Federal infrastructure policy and communications for over 3 years.

Barring statistical inaccuracy (likely), American traffic fatalities ranked 12th on the list of leading causes of death in 2021, just below suicide and just above kidney failure. Of the 15 top ways to die in the US, traffic violence outlies because we know that each and every one of these deaths is preventable. If we invest the same amount into traffic death research as we do in heart disease research, there’s a non-zero chance we can save lives, but when confronted with this fact the road-building machine epidemic (RBME) in the United States scoffs and balks. It’s unAmerican, restrictive, assimilative, and low ROI to invest in safety compared to investing in permanent free-flowing automobile traffic.

Or is it?

Well, like any number it’s all how we frame the argument and how we sell it to a public conditioned to expect nothing less than new roads all the time such that the total time and cost of a trip equals driving as fast as possible to and from a destination. For example, if such a driver were to journey to work almost literally anywhere outside the downtown core of a major metropolitan area, there’s an expectation that roads should be pristine, traffic should be negligible, parking should be plentiful, and interaction should be minimal. The chance of death should be zero—after all, we’ve engineered our motor vehicles to seclude us from the world while driving. The true likelihood of death by existence on any road in the US—really any road anywhere—is decidedly not zero. According to data from the World Health Organization (WHO), the US isn’t even close to the worst offender per 100,000 population. This is a testament to the amount we invest in our roads every year. And still, over 42,000 people died on our roadways in both 2021 and 2022.

The numbers normalized by population don’t tell the story, exactly, because we have to normalize again. Americans drive much, much more than other populations. I (quickly) found an old file and a news article stating upward trends in every category: at least five times as many vehicle miles traveled (VMT) as the next biggest “offender:” Japan. David Zipper, in a piece for CityLab in 2022, wrote this remarkable sentence: “On a per capita basis, Japan had just 2.24 deaths per 100,000 residents, less than a fifth of the US rate of 12.7 per 100,000.” This is an insane stat. We drive 5 times as much as our friends in Japan and they have fewer than ⅕ of traffic deaths. Somewhere in my mind, though I think this is not statistically sound, this reads that Japan is doing 25 times better than us, despite American infrastructure engineers investing hundreds of billions of dollars each year into roadbuilding.

None of this makes rational sense unless we peek under the hood of the conditions that have purposefully led us here: perverse incentives to move as many cars as fast as possible, despite all the evidence pointing away from this being a factor people really care about. (Anecdotally, I’ll tell you that most people care about reliability over speed and you can frame that question to your friends and family, too. Dying on the way to work does not qualify as a reliable trip.)

But we train our road engineers to build for certain road conditions (through “average daily traffic” or ADT scoping and level of service “LOS” metrics—both measure the “free flow” of unimpeded traffic in slightly different ways) and we’ve codified the rules in manuals and guidance that’s lockstep out of step with modern safety and reliability needs. Safety isn’t unimportant per se, and this isn’t totally fair to the generation of traffic engineers who are prioritizing safety on our roads and streets, but when speed trumps all else and we measure and weight return on investment on speed alone, where’s the incentive to change any practice at all? Who’s going to fight, alone, to change a century of embedded, premature death planning?

USDOT is changing its tenor, and with it, state DOTs, city DOTs, and other governments are trying to follow suit. How do I know this? Early in 2023, our national transportation organization issued $800 million to over 500 communities to try to tackle this enduring epidemic. We won’t know the results for a decade or so—as infrastructure changes and shifts so does behavior and it’s a slow-moving machine. But it’s a step in the right direction toward measuring the cost of traffic violence and the benefits of preventing it. It’s about time.

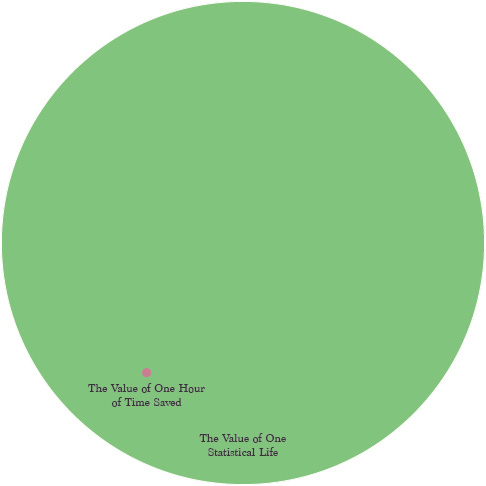

Last point, and it should make a final point to make a case here: we do in fact make the case for traffic safety during the application process for competitive Federal aid. USDOT publishes a guide for conducting a benefit-cost analysis (BCA) that includes specific accounting advice for our two competing priorities: speed and safety. In 2023 the numbers are as follows:

The value of a statistical life (crude and diminutive, I agree): ~$13 million

The value of an hour of general travel time savings: $18.80.

If a project should expect to kill even a single more person per year—widening a highway will do that—then it better damn well save about 700,000 hours of commute time, shaving off about 60 minutes for about 11,500 people annually. If that’s something we’re willing to do—to trade even one life to save an hour per year—then, well, we’re just nowhere.

While I think this touches on some good points I think it misses the forest for the trees a bit. The Federal policy shift must not be contained to transport, USDOT promotes heavily quantitative BCA analysis often based on Crash Modification Factors, CMF's, with very little research to back them up and road deaths are heavily stochastic meaning money is just directed at places where fatalities have occurred and then uses CMF's with questionable effectiveness. While I think its good to pour money into safety instead of congestion management through widening as a first step, a better step would be for the Federal Government to get back into the business of building dense urban housing to simultaneously combat the housing crisis, climate crisis, and reduce VMT per capita. HUD stopped building affordable housing in 1973 under the auspice of Tricky Dick Nixon. On the transport side speed needs to be reduced on streets, notable not on roads, and that should be done whether or not a BCA analysis says its good.