Productivity is at odds with human flourishing

The "time is money" mantra is a terrible starting point for planning and designing infrastructure.

The "time is money" mantra has driven much of the conversation around traffic congestion and sprawl, but it’s a terrible starting point for planning and designing infrastructure.

Traffic congestion is a pervasive issue, whether it’s the destination (downtown, special event, etc.) or the trip to the destination (highways and byways). In economic terms, congestion occurs when demand for roads exceeds the supply of roads. When there isn’t enough space for all of us to get somewhere at the same time, the lanes fill up.

Your time is valuable, and there are prices to pay for sitting in congestion. If you’re late for a meeting, you might miss out on a business deal. If you’re a business owner, surrounding congestion might cause potential employees to work for a competitor instead of you. There are absolutely consequences to roads that are filled up during commuting hours. But it’s a huge mistake to overplay the economic impacts of congestion.

Researchers and academics love to analyze traffic jams in the “time is money” framework, and it’s irresistible for news outlets because they churn out steady doom and gloom headlines.

“Lost productivity cost the US economy $120 billion last year”

“Drivers in this city lose an average of 170 hours of time each year”

“Americans each lost $1,500 last year while sitting in traffic”

Of course an industry that plans, engineers, and builds roads is eager to push a message that we need more roads. (It’s not us, it’s the economy!) But this idea of attaching dollar values to productivity is widespread. The World Economic Forum uses the standard economic analysis of congestion to justify things like transit lanes and bike lanes.

Cities and suburbs benefit from multimodal infrastructure, but this isn’t the talking point we should be pushing. Valuing people for their economic contributions is like standing in a park, seeing only the potential lumber instead of the ecosystem it supports, the biodiversity it houses, or the beauty it offers.

How about this irony: a society that prides itself on individual freedom and opportunity measures individual value to economic parameters.

While economists calculate the billions lost in productivity, less attention is given to what those hours could represent outside an economic lens—time with family, engagement in community activities, or simply moments of rest and reflection. You know, all the stuff we know makes for a higher quality of life.

The productivity pressure creates an environment ripe for anxiety, depression, and burnout, as the fear of falling behind or not measuring up becomes a pervasive force in people’s lives. There’s an expectation to always be "on," connected, and producing.

Admitting to struggling or needing a break is often seen as a sign of weakness or failure, pushing individuals to ignore their body until they reach a breaking point. Too much productivity paradoxically undermines the promises of productivity. You could write lyrics for a country ballad about this stuff: “He tried so hard that he died too soon.”

Corporate human resources know all about this. Workplaces see higher turnover rates, decreased employee engagement, and burnout. A machine running constantly without maintenance will break down. The human body and mind needs frequent maintenance in the form of socializing, resting, and walking with no particular place to go.

As long as we’re living in a productivity-driven landscape, economists will quantify the value of time spent in traffic. Their math will always show a horrific outcome of regions losing billions in productivity. Just remember that math narrowly defines human worth and success. Living like a battery powered machine is hardly flourishing.

There are a million repercussions for putting too much emphasis on productivity, even if the name is sanitized as “work ethic.” There’s one in particular I hope you remember: induced demand.

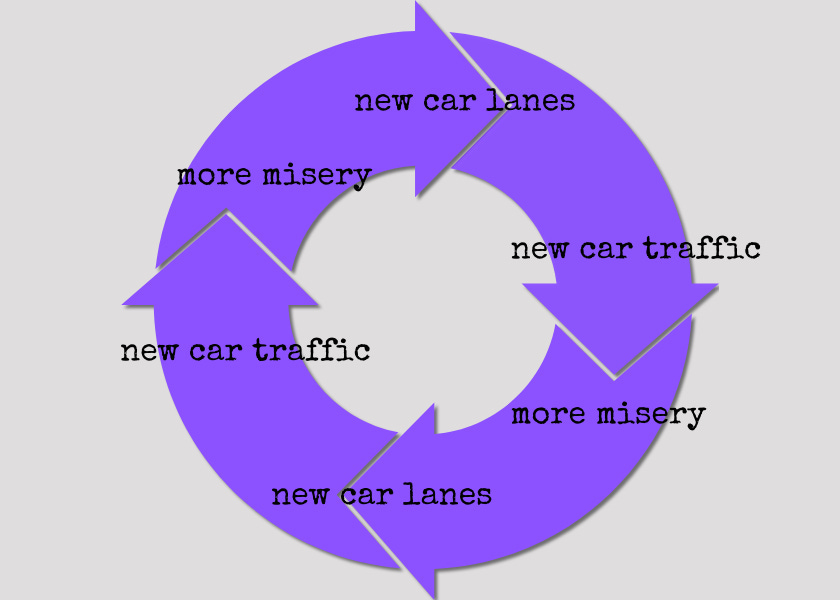

Induced demand means that when the amount of a product is increased, more of the product is consumed. Building more lanes to commute long distances in personal cars incentivizes commuting long distances in personal cars. Every community at and between the two nodes (home and work) pays extraordinary prices for the car dependency.

Road expansions only temporarily reduce traffic congestion, but professionals only temporarily remember expansions don’t work. It’s a brutal and expensive cycle.

It’s no secret that public agencies are strapped for cash, and it’s no secret that public agencies continue to spend depleted accounts on attempts at congestion relief in a futile attempt to reduce traffic. Be highly skeptical of any reports about the economic costs of congestion. From what I’ve seen, those studies reduce humans to soulless machines.

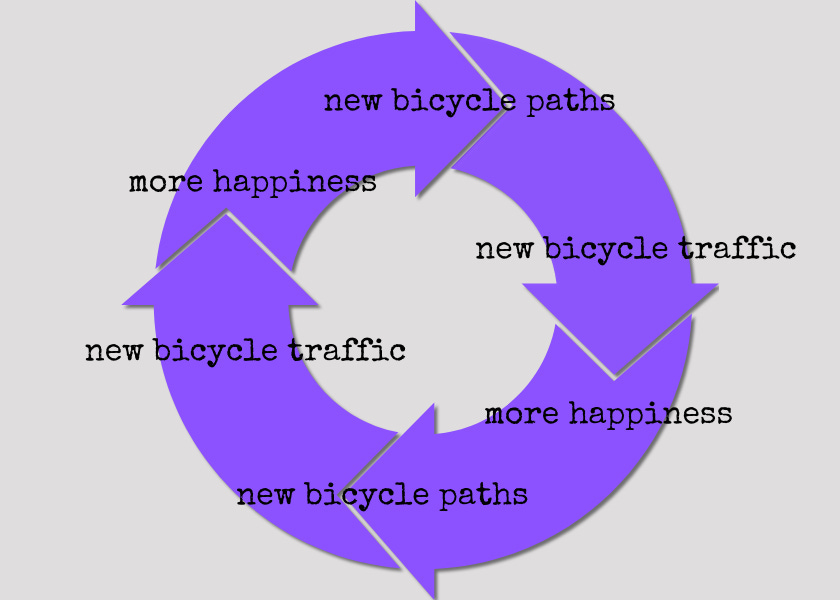

One alternative for economists who track land value, small business trends, and generational preferences is to analyze and report on the opportunities of mixed-use neighborhoods. Start connecting the dots between the social and financial benefits of abundant housing, convenient multimodal options for commuters, and walkable destinations for all ages. Measure the things that don’t show up on a productivity dashboard.

If you plan for human flourishing, you’ll see induced demand in a new way.

I learned a couple of things on a road trip 2 summers ago, one where we had very few time-driven destinations and no deadline about arriving home. (We're at that stage of life where we can either choose to work on a more leisurely schedule or not work at all.)

By deciding to avoid interstates as much as practical (which turned out to well over 90% of the time), I learned about the sheer number of available routes for getting from A-Z across this big country of ours. Old Federal Highway Rt. 2 was one of my favorites. It runs from Everett WA to Houlton, ME, and took us through some of the most beautiful scenic countryside and interesting cities and towns you'd never see if you took the freeway. America looks a lot less generic when you take the old routes.

That experience changed me permanently. I avoid freeways now as a matter of practice when I can. It may be more circuitous but using city streets during congested times rather than sitting in bumper to bumper traffic on the freeway often saves me time.

This has nothing to do with productivity. Just an observation that we have a lot of roadway infrastructure out there that isn't the usual congested routes.

Great piece taking into account the non-pecuniary benefits of good urban planning. As an economist who covers research (a lot on this topic recently of urban house prices and public transit), the research naturally does focus on these pecuniary benefits (whether productivity, income or house value). There is a growing research trend to attempt to estimate a dollar equivalent value of amenities. This makes public transit and even more important cocept. But naturally not all of this can be easily factored/modelled, so we sometimes have to take a stand/guess on the value generated.