Some jobs should be automated

Spare me the sob stories, unless you're prepared to take the anti-automation position to its logical conclusion. I won't agree, but I'll respect you.

Automation is going to take jobs away from humans, and it’s a mistake to think that’s always a bad thing.

It’s childish to pretend any threat to current jobs must be squashed, and that attitude is going to harm the very workers they’re trying to protect. But the approach among alleged grown-ups seems to plug their ears and “la-la-la” when faced with challenging discussions around trade-offs. It’s just so much easier to slap a Good or Evil sticker on a topic.

People who are paid to do tasks that can be done better, safer, and cheaper by technology are always at risk of losing their income stream. This is not new. Where’s the modern day outrage over the Xerox machine? Imagine how many human-powered reports could’ve been handwritten by loyal union members instead of one corporate intern making copies in a machine that also sorts, collates, and staples.

Environmental Impact Studies are notorious for their size. Five years ago, the Council on Environmental Quality took some time to study this because of the widespread delay in projects nationwide.

Based on its review, CEQ found, across all Federal agencies, that for draft EISs, the average (i.e., mean) document length in this sample was 586 pages, and the median document length was 403 pages. One quarter of the draft EISs were 288 pages or shorter (i.e., the 25th percentile), and one quarter were 630 pages or longer (i.e., the 75th percentile).

CEQ also found that, for final EISs, the average document length was 669 pages, and the median document length was 445 pages. One quarter of the final EISs were 299 pages or shorter (i.e., the 25th percentile), and one quarter were 729 pages or longer (i.e., the 75th percentile).

All these 600-page draft environmental studies and 700-page final environmental studies were unfairly printed. You might say the EPA was indirectly involved in stealing jobs away from human-powered labor in favor of automation. The scale is unfathomable.

So it might surprise you to hear the EPA come out swinging against automation over the last few months. Artificial intelligence and large language models are the most recent example of applying a Good vs. Evil (or the milder Us vs. Them) label to emerging technology.

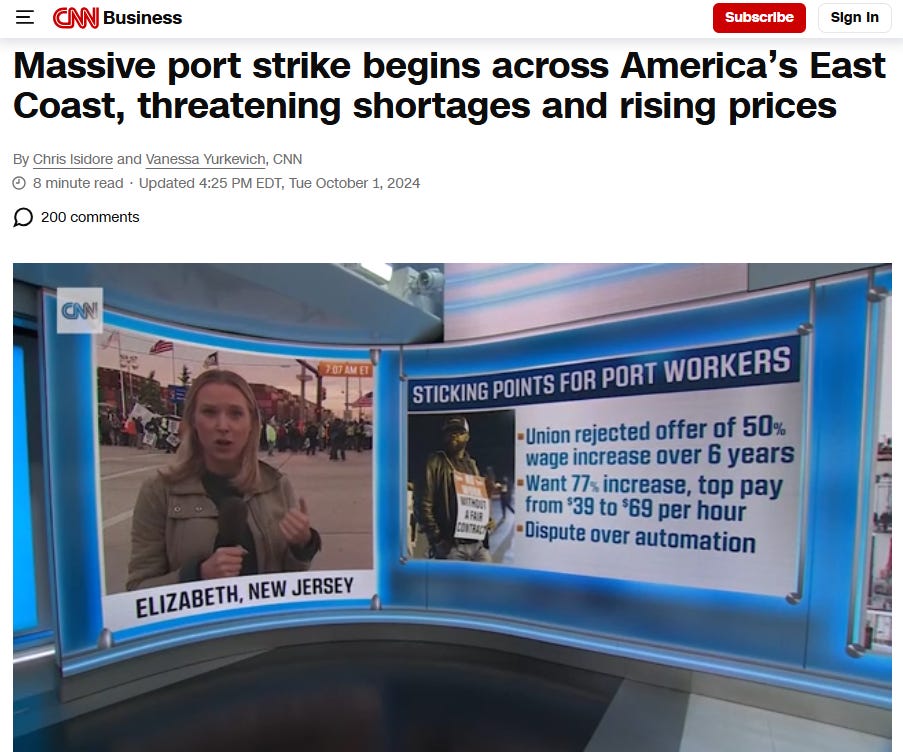

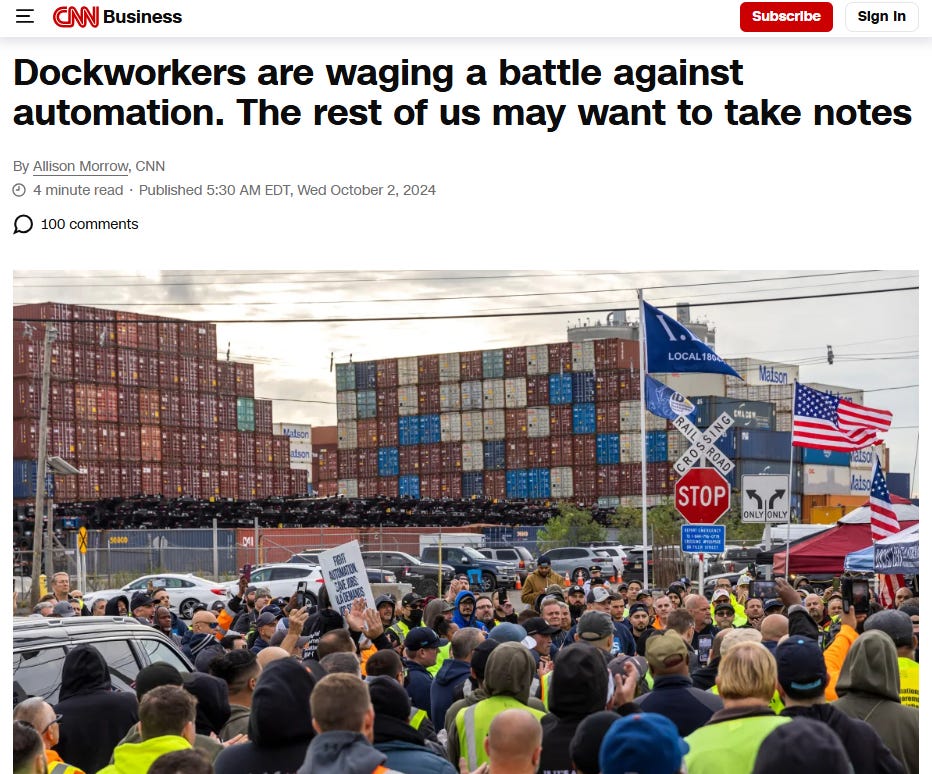

Perhaps you saw headlines about the recent port strike drama:

Union members who work at ports and docks had a comically over-the-top reaction to automation, but the joke’s on the rest of us because they got their way. Hats off to the incredible bargaining power that resulted in the federal government promising to direct their billions of dollars in port grants to applicants that reject progress.

the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) today announced 55 selected applications for nearly $3 billion in Clean Ports Program grants funded through the Inflation Reduction Act. The selected applications will fund zero-emission port equipment and infrastructure as well as climate and air quality planning at U.S. ports located in 27 states and territories. The ILA successfully defended its position that this program and its funding would protect longshore jobs against automation and automated equipment.

The ILA was thrilled about the short-sighted decision:

With the leadership of EPA Administrator Michael Regan…EPA will only fund zero-emission equipment that is human operated and human maintained.

Automation at ports isn’t on the same timeline as, say, human colonies on Mars. Technology is being used right now that can and should replace human jobs.

[cough cough Xerox machines cough cough]

Some easily findable examples on the internet include…

Automated container handling: AI-driven cranes and robotics are transforming container handling at ports. Traditionally, loading and unloading containers from ships have been labor-intensive tasks requiring significant manpower. Automation reduces the need for manual labor and minimizes human error. This accelerates the overall process and means fewer workers need to commute to port facilities, cutting down on vehicle emissions and contributing to a reduction in the port's overall carbon footprint.

Predictive maintenance for port equipment: AI helps predict maintenance needs for essential port machinery like cranes, conveyor belts, and trucks. Instead of relying on human workers to regularly check and maintain this equipment, AI systems use real-time data to predict when maintenance is required. This proactive approach reduces the risk of unexpected breakdowns and extends the lifespan of machinery, which reduces the need for replacement parts and emergency repair missions that consume extra fuel and resources. It’s a no-brainer way to be good stewards of materials and energy.

Optimized workforce scheduling: Automation doesn’t replace all the jobs. AI can optimize workforce scheduling by predicting the busiest times for port operations and assigning workers accordingly. Instead of maintaining a full staff on-site at all times, which leads to inefficiencies and wasted labor hours, AI helps ensure that the right number of workers are present only when needed. This reduces idle time, cuts down on unnecessary commuting, and ultimately decreases the port's energy consumption and emissions. It’s also unpopular among union reps.

Warehouse robotics and sorting: Ports often have large warehouse facilities where goods are sorted and stored before being shipped to their next destination. AI-powered robots are taking over these labor-intensive sorting and packing tasks. These robots operate with precision, drastically reducing the amount of manual labor required and improving the speed of processing goods. With fewer workers required on-site, there are fewer emissions from commuting, and the environmental footprint of the whole operation is reduced.

Traffic flow management: Ports are bustling areas with a complex mix of vehicles, including trucks, forklifts, and personal cars. AI can optimize the movement of these vehicles, reducing congestion and improving safety. AI reduces the amount of time vehicles spend idling or moving inefficiently around the port, speeding up logistics operations and cutting down on fuel consumption and emissions from vehicles that would otherwise be stuck in congestion or performing redundant movements.

Supply chain optimization: AI optimizes the flow of goods through ports, analyzing real-time data on shipments, traffic conditions, and warehouse capacity to recommend optimal routing and storage solutions. This reduces the manual coordination needed to manage complex supply chains, enhances the efficiency of port operations, and minimizes bottlenecks that require labor-intensive troubleshooting. The result is a smoother logistics process that keeps goods moving swiftly with fewer human touchpoints.

If you think I’ve gone too far on the EPA’s hot take on automation, it’s for a reason. These automation examples are just the first ones that jumped out at me while doing a quick internet search. I didn’t even touch on all the ways human error is leading to calamity. Machines are precise. They don’t get sleepy, they aren’t distracted by coworker drama, they aren’t calling in sick the day after the football game, and they aren’t making miscalculations that lead to a waste in resources.

Some jobs should be automated.

The future isn't a binary choice between humans and machines. Automation is inevitable and necessary for a society that values efficiency, safety, and environmental stewardship. When technology can handle repetitive, dangerous, or resource-intensive tasks, clinging to outdated job roles out of tradition only harms progress—and, ironically, the very workers unions aim to protect.

Don’t fall for the Good vs. Evil framing around emerging technology. Machines are stepping in where human limitations make room for error or inefficiency. The short-term answer to people afraid about job loss is to learn new skills. Like the scribes who were replaced by those job-stealing copy machines, some people need to apply their skills in a new way or acquire some new skills.

Absolutely agree with you on this, Andy. Thank you for putting it so clearly. The key is to discern which technologies are appropriate for which tasks (not a trivial exercise). And then find ways of supporting workers who will be losing their livelihoods.

Unfortunately our society has a very poor record with respect to this second aspect of replacing human workers with technology. Disruptive technological progress has a long history of resistance ("sabotage", Luddism, etc.) precisely because it strikes at a person's ability to actually earn a living, while (in theory) increasing the profits of the employer/owner. So what can we do to make this inevitable disruption more humane, and make sure the displaced people have a chance to remain productive and engaged?

For me this is one of the major questions of this century. Technological progress seems poised to replace large numbers of workers. EI and Welfare programs are completely inadequate to handle the scale of the disruption. Are we on the way to some sort of Universal Basic Income?

Re: "some people need to apply their skills in a new way or acquire some new skills".

Automation is an overall boon to society and quality of life. Whether in the home (washing machines, dryers), in industries (floor polishing robots, robot welders), services (automatic espresso machines at Drive throughs), and offices (Spellcheck, autofill). Whether people are at home or at work, the automated devices are doing more work for us.

However, the impacts on displaced workers are arguably much harder on people either lower education and more specificalized job skills, and less hard on people with more education and more transferable skills.

Let's take three people who lose their jobs in 2030 due to automation:

*Pat worked in a printshop running a big 2010s-era binding machine (the PNP-200) that requires lots of complex settings via an input panel. His job was eliminated when a new AI-powered automatic printer-binder unit was purchased. He is 55 and has a high school diploma.

*Mary worked in invoice processing for a major bank, inputting information into the bank's custom-made, proprietary database system, the KLX-9000. She became recognized at the bank for her expertise in resolving the quirks and bugs in the database entry process. She is 55 and has a one year community college diploma in administrative services.

*Kalia worked as a lawyer in a big human rights NGO, doing research in the archives to prepare senior partners for cases. In 2030, the firm purchased an AI program was developed that could take over her job. She is 55 and has a BA and a law degree.

All are unemployed in 2030, but Pat and Mary are going to find it hard to apply their skills in new ways, because their skills are tied to specialized obsolete equipment. Pat's intricate knowledge of the big PNP-200 binding machine and Mary's comprehensive knowledge of the KLP-9000's quirks aren't going to help them get new jobs.

Kalia, with her BA, has a general education which will enable her to get a middle class office job. Even if she can't use her law degree in a legal setting, it will still be seen as an asset for jobs in government. Kalia may end up underemployed, but she will still be able to get a job in a big bureaucracy, as her transferable skills (researching and drafting documents) will be valued there.

Pat and Mary have skills, but these are associated with obsolete equipment. Both developed their skills with this equipment over many years of working. After their layoff in 2030, they are unlikely to find a skilled job with a commensurate pay, and it will be unlikely they can ramp up to a similar skill level on a 2030-era system in their remaining few years of their working life.

Questions:

*Should Pat and Mary get assistance for retraining in 2030, to reduce the risk of unemployment?

*Does being underemployed due to automation mean Kalia should get assistance for retraining in 2030?

*If yes, should it be the company laying them off which pays? Or government?

*Given that the diplomas or degrees that unemployed people need might take 2, 3, or 4 years to complete, from a policy perspective, does it make sense to pay for Bob, Mary or Kalia to go to post-secondary education from 55 to 57 and then retire a few years later?