Stop liking what I like

Urbanism issues are needlessly assigned political labels out of tribalism.

If you came across Urbanism Speakeasy via LinkedIn or Twitter/X, then you’re probably also familiar with Strong Towns. Founder Chuck Marohn and I first met through Congress for the New Urbanism and discovered an eerily similar backstory: traffic engineer becomes plangineer becomes whistleblower. They do great work, especially with regards to fiscal responsibility and economic resilience at the local level.

Current Affairs, a self-described progressive magazine, wrote a weak hit piece on Strong Towns.

“It’s proposed solutions rely on conservative politics.” Ok.

The author and senior editor have been busy defending it on social media, insisting they’re all in favor of coalition building. I’ve given this article too many clicks (1) looking for the alleged substantive critique and (2) looking for how a reader would leave knowing Strong Towns can be an ally for leftists. Neither is there.

I’m not the only one face-palming about the missed opportunity. Historian, professor, and all-around terrific human Peter Norton wrote a response to the Current Affairs piece that frankly I think you should read instead of CA’s. Here’s a taste:

It’s obvious to me that Charles Marohn’s political values differ markedly from mine. I recognize many of my own values in those that are evident in Dean's article. This fact, however, does not lead me to reject Marohn's views, or those of Strong Towns. To the contrary I welcome and value a perspective that often arrives at valid and important conclusions by another path. There's a sense of confirmation in it – like that feeling we may remember from school when we found that you can arrive at a correct answer to a math problem by multiple means.

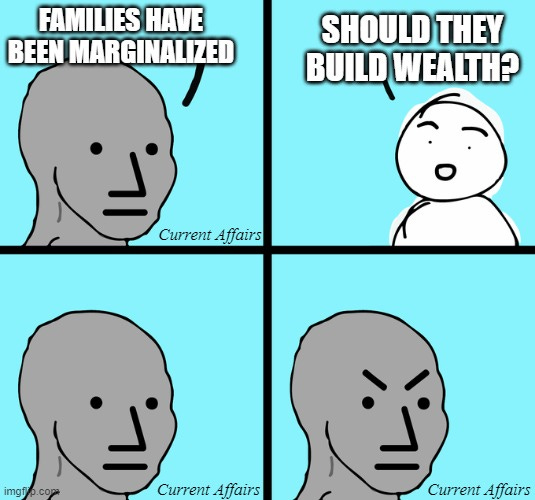

The CA piece signals to readers that ST is not to be trusted based on phrases like “wealth building” and “do the math.” It’s silly but also frustrating because there are so many urbanism issues that are assigned left or right labels simply out of tribalism.

Traffic analysis, street design, transit route planning, building codes, zoning ordinances, land value taxing, housing abundance, universal design, accessibility... this stuff impacts all of us with or without politics. Look at recent housing debates in progressive cities where left NIMBYs and left YIMBYs are debating whether or not small homes should be legalized.

The CA subtitle sneers at wealth creation, which is pretty wild considering how this could be a core position for leftists. Ignoring personal finance and local economies leads to shrugs over devastating practices like eminent domain.

Consider this Alabama story:

Here in Dixons Mills, 75 of our family members live on our homestead, which has been built and handed down over seven generations. We have over 100 years of history here. Our African American and Native American ancestors worked hard as sharecroppers to provide this land for future generations to live on. Today, we use this land to farm, fish, hunt, raise livestock, and run small businesses.

We consider it the base of our freedom and our safe haven. That safety is now being threatened.

Or this California story:

“I learned (in September) about a document that stated my grandfather, who served this country in World War I, and his two brothers would have been prosecuted for not giving their land to the government.”

The Burgesses hope a law that helped a Black Southern California family retain their property will do the same for them and other families they know have lost their land to eminent domain and alleged Whitecapping.

It doesn't matter how the Moore family or Burgess family votes, or if they get involved in politics at all. Centralized planning is crushing them. A magazine like Current Affairs seems like the perfect place to wrestle with the consequences of centralized power, not dismiss them as right-leaning or libertarian or any other label that suggests “don’t take them seriously.”

CA, like many legacy/corporate media outlets, ends up looking hypocritical or intellectually lazy when they could be vocal champions of the oppressed.

Things can get better. Of course it’s possible to find allies from different walks of life. It’s true for sports, business, or land use policy. There are ways to find shared interests with people who at first glance seem to be opponents. With that in mind, here are a bunch of questions a curious person might use as a starting point for talking, writing, or even debating urbanism issues.

Can land use reform be accomplished while remaining politically neutral?

Is wealth creation problematic or a lifeline to the historically marginalized?

What happens when progressives and conservatives find shared interests in community building?

What are some strategies employed by successful coalition builders in bringing together individuals and groups with divergent cultural backgrounds?

Can you identify specific instances where unexpected alliances have emerged across seemingly vast political divides?

What are some driving factors behind famous unlikely partnerships or alliances?

How do consensus-building initiatives navigate the complexities of cultural and political differences to find common ground?

How is it possible that a self-described left-wing activist and self-described right-wing activist can both support roundabouts?

What role does communication play in teaching residents about local economics when they’re from opposite economic backgrounds?

Can two people who literally speak different languages champion the same cause? How does this relate to urbanism?

What are the ethical implications of giving eminent domain power to central planners?

Are there any instances of opposites attracting in personal relationships? Is there a lesson for policy wonks?

Can zoning reform be achieved in a way that fosters inclusivity, regardless of political affiliations?

How can wealth creation be harnessed as a tool to benefit historically marginalized communities?

Are there examples where both progressive and conservative values converge to create better urban environments and stronger communities?

Are there any examples of a community prioritizing economic development and finding the outcomes are also beneficial to the natural environment?

Can community-building efforts bridge ideological gaps and encourage cooperation among various interest groups within cities?

Is it possible for two people with no political similarities to share a taste in music? What are the implications for land use and transportation policy?

We could do this all day. Add yours in the comments.

great piece. you and peter have prevented me from writing an unnecessary third take on this. the CA piece was well-intentioned, but misinformed. this is maybe my least favorite quality--well besides the obvious bad ones.

Disagree. ST’s undermining of coordinated (dare say) big planning is real. And sadly effective in some places.

We cannot hide our heads in the sand about need for truly big thinking. Fiscally constrained planning and big planning can coexist. Not a one size fits all. But ST is being intellectually dishonest.