You need to learn to eat your veggies.

If experts are going to claim to serve the public interest, then they need to deliver on the promise. (Even if it's unpopular.)

The public is you, and you don’t vote in your best interest.

Eat your vegetables. No. They’re good for you. I don’t care. Eat em. No!

People make decisions that run counter to their own interests all through life. Choices about diet, college degrees, career paths, even friend groups. The older we get, the easier it is to look back at our life and admit (and laugh about) decisions that did not serve our own interest.

“Serving the public interest” sounds like a noble phrase stamped on local government letterhead or painted on the door of the public works trucks. It rings of “we’re here for you.” For me, it became one of many bits of jargon that I heard so often I didn’t pause to think about.

Here’s a definition of “public interest,” courtesy of Law Insider:

Public interest means demonstrable environmental, social, and economic benefits which would accrue to the public at large as a result of a proposed action, and which would clearly exceed all demonstrable environmental, social, and economic costs of the proposed action.

The tension between what you want and what you need.

In the urbanism context, serving the public interest has nothing to do with opinions about what a community likes or dislikes, but what’s good for them. Policies and projects are supposed to be held to a clear benefit/cost standard. For anything done, prove the benefits are greater than the costs.

Infrastructure professionals get credentials from groups like the National Society of Professional Engineers, American Institute of Certified Planners and the American Institute of Architects. Each has a code of ethics that makes clear that professionals are expected to use their judgment to serve the public interest.

And yet, infrastructure professionals regularly break their oaths to serve the public interest.

Each person is ultimately responsible for their own actions, but there are outside forces weighing heavily on architects, planners, and engineers. I understand the conflict – I was surrounded by it for 20 years. But this is an ethical problem facing thousands of professionals on every project they work on.

“Neighbors divided over roundabouts”

This article about a California community could’ve been written yesterday in any region of the U.S. It has all the standard ingredients:

Engineers propose a design to make an intersection safer.

Engineers survey the community and find a majority support the roundabout.

Neighborhood association reports that a majority oppose the roundabout.

“We resent this being pushed on us.”

Ambiguous conclusion about the fate of the proposed design.

“Neighbors divided over bike lanes”

Washington, DC has steadily expanded its bicycling network, but that doesn’t mean all the residents are happy about it. Does this sound familiar?

Engineers propose a design to make bicycling safer.

Engineers survey the community and find a majority support bicycling infrastructure.

Neighborhood association reports that its members oppose bike lanes near them.

“They’re shoving this down our throats.”

Ambiguous conclusion about the fate of the proposed design.

“Neighbors divided over how many people should live here.”

Residents in San Jose, CA are asked to chime in on the types of housing that should be allowed.

Planners propose housing options that would allow more people to move in.

Planners survey the community and find only a quarter support the housing initiative.

Advocates for and against debate the impacts of density.

Ambiguous conclusion about the fate of legalizing more housing options.

Wishy washy leadership makes everything worse.

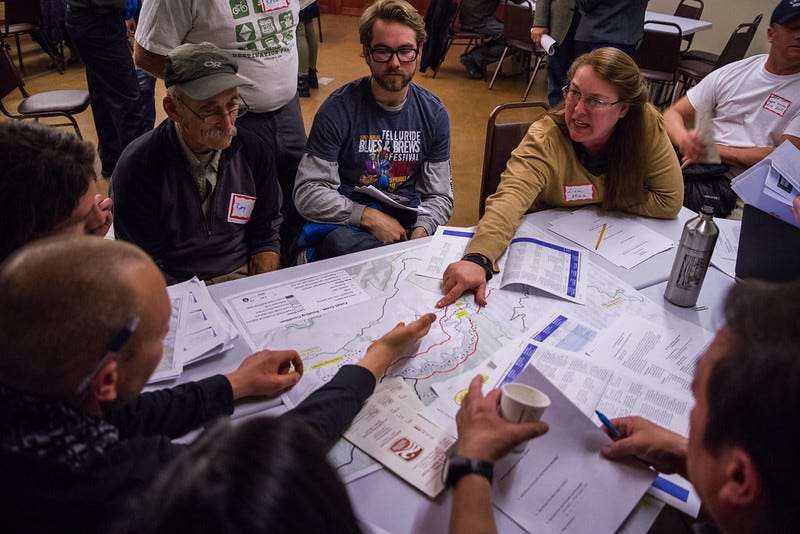

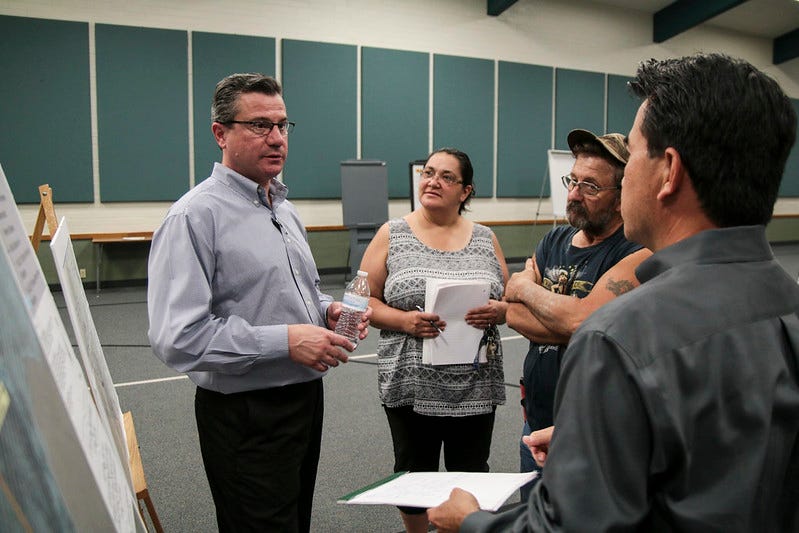

Architects, planners, and engineers are expected to present everything they do in public meetings. But what happens next is fuzzy. Sometimes it’s an education campaign. “We’re restriping the street. It’s going to have bike lanes, but no parking. Here’s why.” Other times it’s a popularity contest: “We’re thinking about legalizing front-yard businesses. What do you think?”

Nobody ever knows what tips the scales for a decision. For any given project, is the public agency serving the public interest or serving the public opinion? I’m not declaring it’s always right to choose one over the other. But I am declaring it’s wrong to claim “public interest” and then not follow through.

Roundabouts, bike lanes, and housing options all have a proven track record of delivering a positive benefit/cost ratio. As a default position, assume those things are in the public interest. And as another default position, assume people don’t like to eat their vegetables at first.