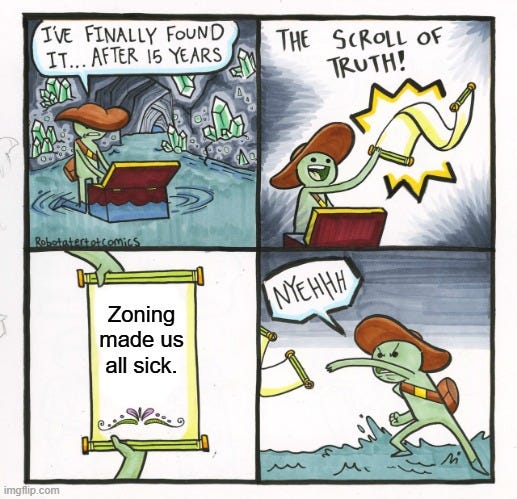

Zoning broke our brains

Legalizing healthy infrastructure is the first step in the path to recovery.

Our built environment contributes to a mental health crisis. We’re not living in a natural outcome of human needs and behavior.

The built environment as we know it—buildings and the spaces between—does direct damage to our minds. Land use planning has had devastating impacts on Americans: economically, socially, and culturally. But I’m not a doomer and I know these things are fixable. Not overnight reversible, but certainly fixable.

Typical land use rules are written, updated, and enforced at the local government level. And as you might expect, agencies copied each other over the years because why wouldn’t they. Years ago, when I learned some photography techniques that were new to me, I made cheat sheets for other photographers. Much of what I’ve learned as an adult (podcasting, publishing, public speaking, etc.) has been taught by generous people who themselves had learned tips and tricks. So of course public agencies copied each other with their rule-making. “That worked for a similar river city? Let’s try it here.”

Planning departments at city and county levels weren’t setting out to guide development in a way that would purposefully harm people. Quite the opposite.

If a new Sears distribution center was coming to town, they’d want to map out a plan to accommodate all the new employees and subsequent traffic. In the middle of the 20th century, planners were still very much concerned about separating dirty and/or dangerous land uses from residential areas. The result was that all across the country, local development rules required or incentivized development patterns that spread everyone and everything across the landscape.

A work zone, school zone, shopping zone, entertainment zone, and a sleep zone were established. And then each major category started getting more prescriptive sub-categories. “Residential” morphed into single-family, multi-family (apartments), and condos. But wait, there’s more! Residential land uses started to be regulated by local governments according to lot size: garden apartments, planned unit developments, and subdivisions were each given rules. Residential was also regulated by the type of people living in a place: public housing, group dwellings, age-restricted dwelling, renters, and owners.

Local regulations created—and continue to create—sprawled out development patterns in cities and suburbs.

The car-dependency factor

Land use planning requires traffic engineering analysis, a process prioritizing speedy car movement above all else. Wider roads and intersections are not just suggested but required with the express goal to move vehicular traffic from zone to zone as quickly as possible. This has been going on for nearly 100 years without taking a foot off the brake.

The obvious outcome of modern land use planning is that Americans drive everywhere all the time. Not just work commutes, but all the errands before, during, and after work. Half of our car trips are less than a few miles long. A quarter are less than one mile. Less than a mile in a car by ourselves.

The mental health crisis

Life in a single occupant vehicle has its perks, like singing along to music or listening to podcasts uninterrupted. It also has its pains, like separation from other humans and mental deterioration.

Loneliness is a significant variable affecting depression. It’s a predisposing factor. Cigna conducted a study of 20,000 Americans, and reported a jaw-dropping finding: nearly half of adults sometimes or always feel alone. 40 percent said their relationships aren’t meaningful and they feel isolated.

Dr. Julianne Holt-Lunstad is a professor of psychology and neuroscience at Brigham Young University. She says the health risks of missing out on social connection is like smoking 15 cigarettes a day.

Worse yet, there’s a causal relationship between social isolation and suicide. Conversely, having a crew (“social support” in doctor jargon) has a protective effect against suicide. For every suicidal death, another 20 people attempted suicide.

So what can you do with this heavy information?

First, remember that the built environment is deliberately planned for us to drive in cars from zone to zone. Planners aren’t trying to destroy our minds, but the built environment increases anxiety, depression, isolation, loneliness, and suicide.

Second, understand the land use catastrophes are reversible. Compact development won't be legalized overnight, but reform can come as quickly as local leaders are willing. Walk-friendly, bike-friendly, transit-friendly places are good medicine, and they’re made possible at the local level.

Third, and most important of all, know that things can get better in the end. America’s built environment does not fit who we are as humans, but we can turn this around with something as boring as reforming land use planning. Start by legalizing healthy infrastructure—a variety of land uses within walking distance of homes and streets designed for safe walking and cycling.

Thanks for the article! I really appreciate the "what can we do with this information" section of the article! I personally think we're too gentle with zoning. At this rate, I think a fair approach is to drop zoning as it stands now wholesale, address sincere and worthwhile concerns (i.e. - NOT "to preserve existing neighborhood character" generally) as they present themselves in an ad hoc way, and establish new rules and regulations for the things that recur.

When adding mixed uses to a longtime leafy suburb (single family homes only), there will be benefits for residents. When the first cafe is built, there will be a place that people can walk to for coffee dates or friend meet-ups. When the first licensed bistro is built, there will be a place that pals can walk to for a beer and a burger. When the first low-rise apartment building is built, there will be smaller, less expensive housing units in the neighborhood, places for retired couples to move to (thus freeing up their five-bedroom house for a young family), or for a young, early career person (who can't yet afford a big house) to move to.

As much as I support your mixed land use arguments, I think it's important to analyze and address NIMBY concerns associated with each of the new mixed land use examples that were given.

Let's start with the lowest-impact example--the neighborhood's first cafe. It's a relatively low-impact example, because it's not licensed (so there's no risk of drunken, noisy patrons). As well, most cafes are only open during the day, so it won't create traffic congestion or noise in the evening. However, even this quiet café will have negative impacts on the houses immediately around it. Let's say the cafe has excellent coffee and tasty, fresh baked goods, so as the only location in the neighborhood, it attracts a steady flow of cars. Local residents now face delays in their commutes and the on-street parking is filled with patrons on both sides of the streets. This leads to nearby residents complaining about the cafe at a neighborhood meeting. The cafe-loving residents who live many blocks from the cafe get to enjoy the coffee and muffins, but don't experience the impacts on their street.

A few streets down, the neighborhood gets its first licensed bistro. As with the cafe, it proves to be a hit in the neighborhood, as now you can walk to get a beer (and walk home without incurred a DUI charge). However, the residents who live right by the bistro are upset at the increased traffic, on-street parking, and noise from patrons talking loudly on the patio. As well, there are complaints about patrons talking loudly as they leave the bar at last call.

With the neighborhood's first apartment building, the developers provide one parking space for each unit, but most couples have two cars and couples with college-age children even have three vehicles. As a result, the on-street parking around the apartment is always full, leading to concerns from the single family home dwellers, who used to have lots of on-street parking available for their second and third cars (and their visitors). As well, homeowners near the new apartment point to traffic studies showing an increase in traffic associated with the new apartment.

As a YIMBY, I support mixed land use and zoning deregulation. But we need to acknowledge that adding mixed land uses will negatively impact some existing residents and find ways to mitigate or resolve those issues.

For the new cafe and licensed bistro, one mitigation measure would be a limit on the number of tables/seats and on opening hours. As well, there could be a limit on how many on-street parking spaces cafe or bistro users could use, to ensure that nearby residents can still have a spot for guests to park (the implementation of this would be more challenging, but perhaps some spots could have signs up indicating that they are for non-cafe/non-bistro use only).

For the new apartment building, there are two issues that were examined: crowded street parking near the building and increased traffic. If the apartment building was developed alongside a mixed transit plan (bike path to light rail stations; new bus stops aligned with apartment resident needs; car-share parking added for "pay by use" cars), perhaps there would be less issues with apartment dwellers adding traffic and stored vehicles on the nearby streets.