The problem of EV charging

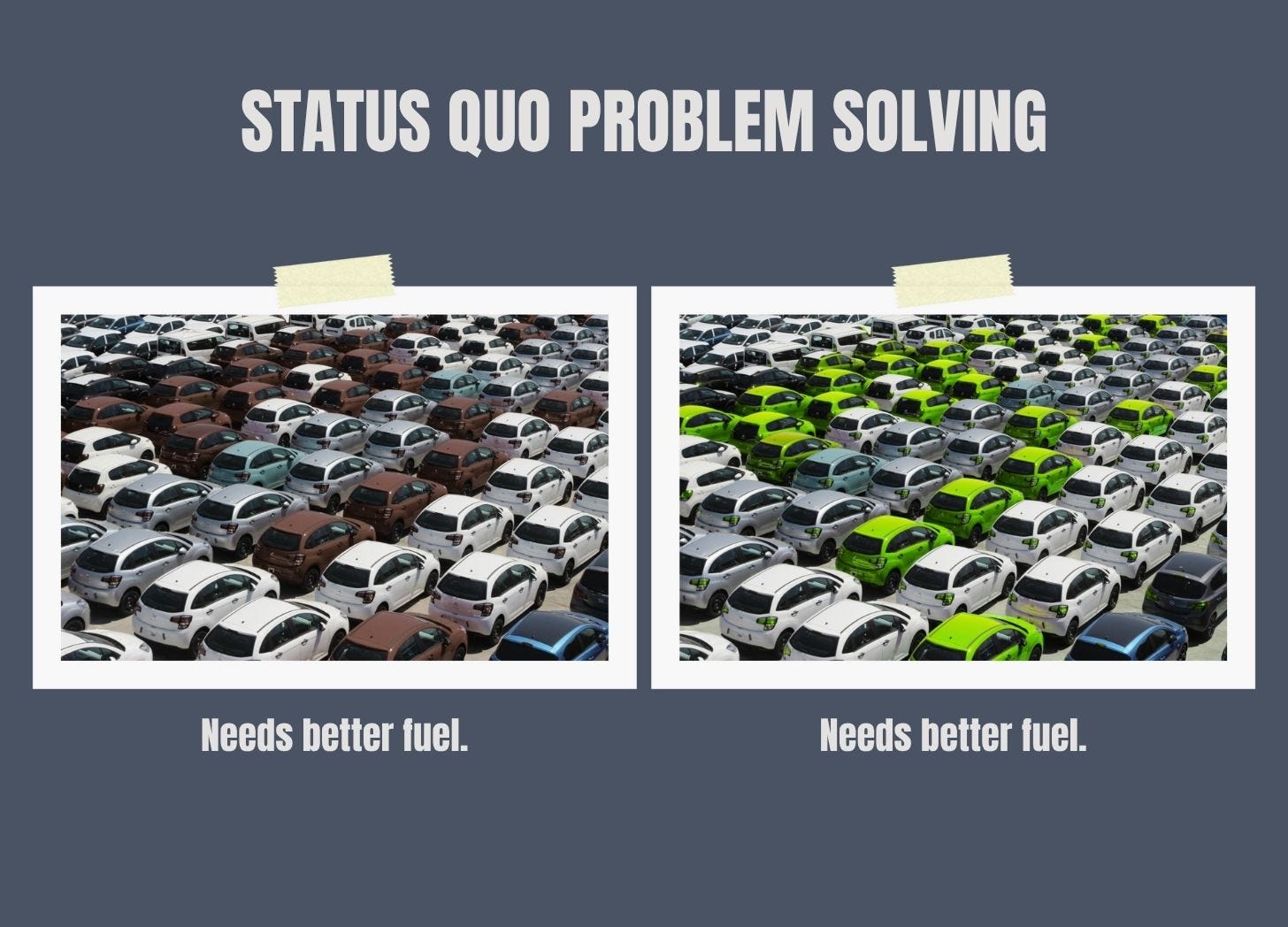

The electric vehicle conversations are overlooking a mobility problem.

You’ve probably heard the famous quote attributed to Henry Ford: “If I had asked people what they wanted, they would have said faster horses.” Regardless of who first said it, that quote is a reminder that history is full of examples illustrating why it’s so important to fall in love with a problem (mobility), not a solution (faster horses).

Sylvanus Freelove Bowser was an inventor and entrepreneur. One of his gigs was selling kerosene, and he saw the potential of gasoline as a fuel source for cars. Automobiles were just starting to gain traction in the late 1800s, and people were struggling with convenient ways to refuel the newfangled machines. Gas was sold in cans and barrels—not exactly the safest or most efficient method. In 1885, Bowser invented a self-measuring pump. No more clumsy cans or precarious barrels.

Even with that success, Bowser wasn't satisfied with the pump. He figured that if gasoline was going to become a widespread fuel source, there needed to be dedicated places to refuel. So, he set his sights on creating the first-ever gas station. He was in a race with big corporates like Standard Oil Company, but Bowser's invention laid the groundwork for the whole concept of gas stations.

Bowser's gas pump was a simple innovation, but as you know, it had a major impact on the world.

It was self-measuring, which meant that drivers could dispense the exact amount of gasoline they needed.

It was gravity-fed, which meant that it did not require electricity or a motor.

It was made of durable materials, which made it resistant to damage.

It was easy to use, even for people who were not familiar with gasoline.

He didn’t start with a solution of “handheld pump.” He fell in love with a problem—refueling is gross and dangerous—and then tested ideas to minimize the problem.

That outlook on problem solving is relevant to the shift from gas-powered to electric-powered vehicles. In early 2023, there were about 100,000 public charging stations. Biden’s infrastructure bill included $7.5 billion to get to 500,000 stations by the year 2030.

Charging stations vary:

Level 1 is the slowest, and they can take several hours to fully charge an EV. These are the ones you’d find in homes and office buildings because there’s no rush.

Level 2 is faster, but they can still take an hour to fully charge an EV. You’ll see these in shopping malls and parking garages.

DC fast chargers take about 20 minutes to fully charge an EV. These are popping up along highways and in other high-traffic areas, but there’s hardly enough for a nation of drivers who crave convenience.

There are a lot of issues that spring out of the need (is it a need?) for fast charging. Considering half of America’s car trips are under a few miles, a robust bicycle and/or transit network would nudge behavior out of personal cars. When I read headlines about charging networks, I’ve been thinking about (and I hope city planners are thinking about) falling in love with the problems.

Bowser’s gas pump was intuitive, but the primary pain point he relieved was customer convenience. In his case, gas barrels were disgusting and dangerous. Today, Americans want everything fast faster fastest. I worry that if the primary focus of EV infrastructure is superfast charging, that we’ll be continuing the saga of car dependency. It’s a subtle admission that “we know you’re going to keep driving, and we’re fine with that, as long as it’s not gas powered.”

Driving’s expensive. Traffic is dangerous.

But for now, if you follow the money, EV infrastructure is connected to the automobile industry rather than bicycles.

E-bikes have been outselling electric cars 2:1. In 2021, there were over 4 million e-bikes sold worldwide, compared to just over 2 million e-cars. E-bikes are still a relatively new technology, but they have the potential to revolutionize the way we think about transportation. Bike share operators across the world are upgrading to e-bike fleets as fast as they can because that’s what most customers want.

EV charging hubs could be thought of in completely different ways. Mobility hubs of the future might look like today’s gas stations, but they don’t have to.

Cars, bikes, scooters, mopeds, skateboards, and golf carts will all need to be charged, but at various levels and durations. Some hubs could be as modest as a bike share station. Some might be adjacent to a university book store. Some might be a sheltered park and ride. Some might be along what used to be a car lane on an over-built arterial. Why not? You don’t need a 6-lane arterial through the suburbs. Put some of that excess curb space to good use.

The problem to fall in love with isn’t “we need more superchargers.” Sure, those will do some good. But the underlying problem is more like “we need infrastructure to support healthy mobility.” Various types of car chargers will be part of the infrastructure, but “healthy mobility” keeps our eyes on human flourishing.

We need some versions of Mr. Bowser who come up with ways to nudge behavior towards healthy living as they plan and coordinate EV infrastructure.

We need a common e-bike charging interface. With that, e bikes could be lighter and cheaper, not needing nearly as much range.

Well in some cases, nothing but a fast charger will work. This week a friend and I want hiking at a trailhead >100 miles from home, and 6,000’ uphill. One of our cars was in the shop so I asked my friend to drive. Well, her EVs range wasn’t sufficient for the round trip, and the mountain town had no fast charger—and of course not even a slow one at the remote trailhead. So we ended up taking one of our ICE cars in the end.

Remote trailheads are a use case that I don’t see EVs serving for a long time—and of course bikes won’t work.